Here in Silicon Valley, the term “leadership” is usually discussed with regard to effectively running and managing an organization — both of which are crucial to becoming a successful founder. But great leadership — whether in business, politics, academia or organized religion — demands more than a thin commitment to managerial efficiency. A deep concern of mine is that leaders in the technology sector have not developed a culture that insists upon courage, honor, duty and humility– what we might call a culture of virtue. The great lesson of leadership handed down to us from classical thinkers in every culture is that those who handle power must do so with a deep sense of responsibility for those whose lives they touch. One of my favorite passages on leadership comes from Sun Tzu, who writes:

Leadership is a matter of intelligence, trustworthiness, humaneness, courage, and discipline … Reliance on intelligence alone results in rebelliousness. Exercise of humaneness alone results in weakness. Fixation on trust results in folly. Dependence on the strength of courage results in violence. Excessive discipline and sternness in command result in cruelty. When one has all five virtues together, each appropriate to its function, then one can be a leader.

Creating a billion dollar company is hard, but being a truly great leader is even harder. It requires an acrobatic balancing of commitments to stakeholders and employees with broader commitments — civic, patriotic, and global. A true leader must strive towards a grand vision of human progress, but remember that the minor details of her everyday life really matter to those who look up to her as a role model. Great leaders must understand how to act in such a way that they exhibit all the virtues in unison.

Great leaders inspire incredible loyalty in their followers and subordinates. In the 6th century, Confucius counseled, “Let him preside over them with gravity; then they will reverence him…Let him advance the good and teach the incompetent; then they will eagerly seek to be virtuous”. There are not many figures in Silicon Valley who viscerally attract followers in this way. In the tech sector it is common to find lost souls who hop from job to job, self-optimizing as quickly as possible instead of striving together towards common goals. Many would-be leaders, overwhelmed by promises they’ve made and expanding duties, go silent on allies and retrench on responsibilities. They put short-term practicalities ahead of honor and virtue. Without a conscious culture of leadership and peers to hold them responsible, executives under the increasing pressure of difficult jobs often give in to lower impulses unworthy of their own leadership potential.

Of course there are a few great leaders with legions of proud followers; there are large groups pursuing bold missions, courageously standing up to difficult challenges and making the right decisions. But these men and women are rare finds in the world of technology, and too few here are striving to understand and emulate their values. There are at least one hundred classes and meet-ups on business or tech infrastructure strategy for every one on leadership.

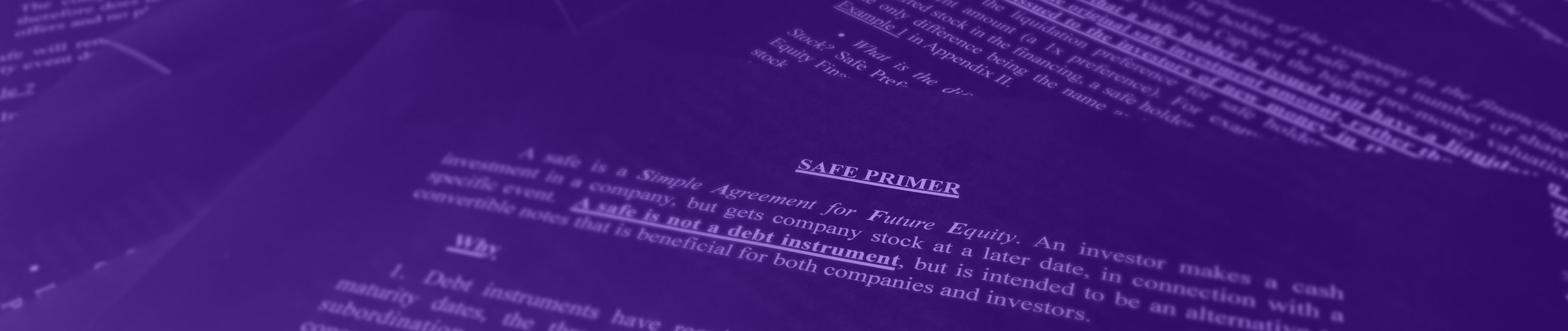

It’s no wonder that when entrepreneurs achieve success, they often arrogantly flaunt their newfound wealth or mistreat others with secretive or unfair liquidation preference-structures, as if their employees or former colleagues are mere instruments to securing greater personal profit. The startup mentality is intensely competitive, and fosters a spirit of “us v. them”. Taken to an extreme, this mentality can manifest itself as ruthless selfishness on the part of founders; of naked, vain ambition rather than the pursuit of a higher purpose. These kinds of viciously imbalanced worldviews reflect a culture that is crying out for stronger leaders. I’m reminded of a line by Cyrus the Great, the wisest ruler in the Persian tradition: “Success always calls for greater generosity — though most people, lost in the darkness of their own egos, treat it as an occasion for greater greed.”

One challenge in building leaders is what you might call the “cult of the engineer.” Our culture strongly (and correctly) emphasizes the importance of developing hard, technical mastery in computer science and related fields. No great companies here are built without a star tech culture featuring a core of elite computer scientists. Meanwhile the more intangible quality of good leadership is brushed under the rug. There is a noticeable gap between most young geniuses who excel in math and science and those who demonstrate leadership ability. It may be that the learning curve to become a sophisticated engineer is so steep that this generation’s brightest don’t have enough time to study the great leaders of antiquity, consider their place in the world from political and philosophical perspectives, or even do things as simple as playing team sports.

Building a startup that outclasses the competition may require a myopic focus on developing a sound product, but leading a company that will change the world requires just the opposite. Henri Fayol — one of the pioneers of management theory — wrote at the turn of the 19th century that “a leader who is a good administrator but technically mediocre is generally much more useful to the enterprise than if he were a brilliant technician but a mediocre administrator.” This is because leadership requires an imaginative awareness that grasps one’s environment as completely as possible, even if only imprecisely. To borrow a phrase from Isaiah Berlin, great leaders have “instinctive skill”; the power to make “inspired guesses” at the best methods to influence others and bring about their vision. George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Winston Churchill all possessed the power to understand the world in a broad, interdisciplinary ways — and this power to synthesize information from every quarter made them extraordinary leaders. We witness the same capacity in titans of industry and remarkable CEOs — Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Steve Jobs all certainly possessed it. For an engineer gifted at coding with mechanical precision, a transition to a pure leadership role will involve a transition to a very different mode of perception — as well as a host of new interpersonal skills.

Benjamin Franklin, American Founding Father, 1706–1790AD

Benjamin Franklin, American Founding Father, 1706–1790ADSilicon Valley needs to address its deficit of leadership. Initially, this will mean raising dialogue about the issue in various forums: technology summits, universities, and individual discussions. Young engineers who want to be successful on a macro-scale should understand that leadership is a skill to which they must aspire — however fuzzy a concept. For those of us in positions of leadership here in the valley, the issue demands both reflection and action. We need to help train and mentor younger leaders at the same time that we think hard about how we can best emulate history’s great leaders and heroes. What can we do to be better leaders ourselves, and to inculcate these values in our organizations and young talent? I hope this is something we can discuss more openly and more often, as Silicon Valley becomes more influential around the world.

There is an enormous literature on leadership — here are a few books we highly recommend, ranging from classics to modern leadership texts:

“Xenophon’s Cyrus the Great: The Arts of Leadership and War.” Ed. Larry Hedrick. St. Martin’s Press, 2006.

Marcus Aurelius. “Meditations.” Trans. Gregory Hays. Modern Library Edition, 2002. Print.

Sun Tzu. “The Art of War.” Trans. Lionel Giles, Chiron Academic Press, 2015.

Benjamin Franklin. “The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin.” Dover Publishing, 1996.

Herman Hesse. “Siddhartha.” Trans. Joachim Neugroschel. Penguin Books, 1999.

Dale Carnegie. “How to Win Friends & Influence People.” Simon and Schuster, 1936.

Peter Drucker. “The Effective Executive.” Peter F. Drucker. Harper Collins, 1967.

Steven Covey. “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.” Free Press, 2004.

John Wooden. “Wooden on Leadership.” Ed. Steve Jamison. McGraw Hill, 2005.

Great thinkers the world over and from every time period have reflected on the concept of leadership. Here are some of our favorite quotes on the subject:

“The highest type of ruler is one of whose existence the people are barely aware.

Next comes one whom they love and praise.

Next comes one whom they fear.

Next comes one whom they despise and defy.”

-Lao-Tzu (5th-4th century BC)

“Whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be servant of all.”

-Jesus Christ, (Mark 10:43)

“The source of this predominance was not barely his power of language, but, as Thucydides assures us, the reputation of his life, and the confidence felt in his character; his manifest freedom from every kind of corruption, and superiority to all considerations of money.”

-Plutarch, writing of Pericles (1st century AD)

“There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.”

-Niccolo Machiavelli (16th century)

“Strive to be the greatest man in your country, and you may be disappointed. Strive to be the best and you may succeed: he may well win the race that runs by himself.”

-Benjamin Franklin (18th century)

“If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader.”

-John Quincy Adams (18th century)

“The greatest moments in the struggle of single individuals make up a chain, in which a range of mountains of humanity are joined over thousands of years.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche (19th century)

“To be a king and wear a crown is a thing more glorious to them that see it than it is pleasant to them that bear it.”

-Queen Elizabeth (20th century)

“One’s philosophy is not best expressed in words; it is expressed in the choices one makes… and the choices we make are ultimately our responsibility.”

-Eleanor Roosevelt

“If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.”

-Antoine de Saint-Exupery (20th century)

“If you just set out to be liked, you will be prepared to compromise on anything at any time, and would achieve nothing.”

-Margaret Thatcher (20th century)

“Management is doing things right; leadership is doing the right things.”

-Peter F. Drucker (20th century)