With a prison population of 2.3 million inmates, the United States has the highest incarceration rate of any country in the industrialized world. On the face of it, housing one quarter of the world’s prison population costs America $80 billion a year.[1][2] But in fact America’s incarceration nightmare represents a true opportunity cost of hundreds of billions of dollars a year, and unnecessarily devastates many of our most vulnerable communities. A major problem is that prisons are incentivized to “warehouse” prisoners rather than provably reintegrate them into society. A competitive, market-based rewards system for private prisons would encourage talented entrepreneurs to help convicts into society in compassionate, effective ways and allow the very best rehabilitation strategies to spread.

The US incarceration rate multiplied by 700% between the 1970s and the present as America abandoned rehabilitative models of criminal justice for more punitive responses. This surge in convictions was partially precipitated by a global crime wave in the 1980s. But the incarceration rate has remained extraordinarily high even though the crime rate has decreased 45% since the early 1990s.[3][4][5]

[6]

To tackle prison overpopulation our country must address a host of issues including aggressive public prosecution, the failure of the war on drugs, exorbitant sentencing guidelines, and the fact that 94–97%[7] of charged criminals opt for plea bargaining over a jury trial. But one obvious strategy for decarceration is to reduce the recidivism rate, or the rate at which criminals reoffend and wind up back in prison. We need to shift from a “custody” model of detention to a “treatment” model. Private prisons, properly incentivized, may be the answer.

Today 8% of U.S. prisoners are currently detained in private prisons (though disproportionate press coverage would lead one to believe that the figure is much larger).[8] The largest private prison operations today are CoreCivic (formerly the Corrections Corporation of America) and the Geo Group, which have achieved a duopoly over the private prison market.

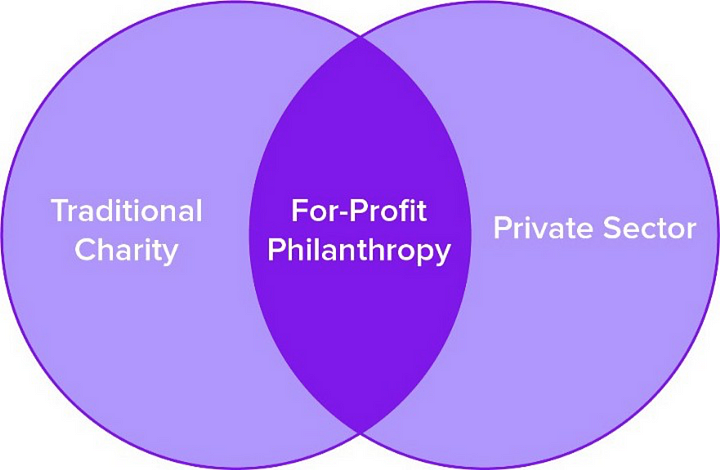

Private prisons gained a poor reputation as early as the late 19th century for subjecting prisoners to barbaric treatment and lax security, but today private prisons are roughly as humane as public prisons.[9] Evidence as to whether private prisons are better than public prisons at reducing recidivism is inconclusive, and a meta-analysis found that private prisons even cost about the same as their public counterparts.[10][11][12] The central problem is that private prisons, like public prisons, are payed on a per-diem/per-prisoner basis. Under this statutory regime, “privatization can come to resemble an exercise in who can better pretend to be a public prison.”[13]

We propose that private prison contracts tie financial incentives to performance measures such as reducing inmate recidivism. If entrepreneurs were given clear lanes to erect new private prison businesses and explicitly incentivized to reduce recidivism, they would experiment with new modes of rehabilitation to find the best ways to reintegrate convicts into society. Operating in a more competitive, transparent environment would force private prisons to rapidly innovate and develop new techniques for rehabilitating the maximum number of prisoners. Private prisons could escape their legacy of mediocrity and brutality by embracing this new mandate.

The first country to experiment with this model was the United Kingdom, which raised a social impact bond in 2010 to fund a rehabilitative program for short-term inmates at a private prison in Peterborough.[14] On this model, investors in the bond were rewarded on the condition that Peterborough Prison reduced the frequency of reconviction events by more than 10% relative to a public prison control group. Investors partnered with the prison to supply paid caseworkers, specialist practitioners, gym volunteers from nonprofit organizations such as the YMCA, and other 3rd parties. These workers engaged in a pragmatic, flexible style of relationship-based therapy, and successfully reduced the recidivism frequency by 11% even while recidivism frequency rose 10% in the control group (2010–2014). Similar programs have been piloted in Massachusetts, New York, Australia, and New Zealand.[15][16][17] These projects are only the beginning — in an evolving market framework the most refined, effective prisoner rehabilitation programs could eventually scale to deliver recidivism reductions on the order of 50% or more.

There are a variety of ways to set up an incentive structure aimed at reducing recidivism. We favor rewarding private prisons with a combination of financial payouts and new inmates to replace the old inmates who will not return to prison. The contract could replace traditional per-diem/per-prisoner rewards with scalar incentive payments that vary with the percentage of the inmate population that doesn’t reoffend over some period (e.g. 2 years). Another possibility is to reward the prison with a flat bonus such as $11,000 per rehabilitated prisoner,[18] or to make upside for prison staff contingent on running successful programs and spreading ideas that work.[19] Many state legislatures explicitly encourage pay-for-success models, and these states should begin experimenting immediately.[20]

Private prisons should only house inmates who will be released in a relatively short time period (e.g. <5–10 years). Prisoners sentenced to life or virtual life would not be eligible for rehabilitation, and it would be unfair to force a private prison to house a convict for whom they have no expected financial upside.[21] Each private prison’s population should be compared against a representative, comparable population in a private prison, or against historical re-offense rates. As a safeguard against mistreatment, prisoners could be allowed to opt out of the private prison and into public prison every 6 months, and would be able to express their grievances in public fora.

Operating in a more competitive, transparent environment would force private prisons to rapidly innovate and develop new techniques for rehabilitating the maximum number of prisoners. Private prisons could escape their legacy of mediocrity and brutality by embracing this new mandate.

Strategies for reducing recidivism are virtually endless — the challenge is to create incentives to make sure the best ideas are documented and spread. We strongly believe in the value of prison-work programs where inmates receive either pecuniary or in-kind rewards — for instance better food, more time in the prison yard, better access to books, and more.[22] Educational programming, employment programming, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), chemical dependency treatment, sex offender treatment, mental health interventions, domestic violence/family life programming, and prisoner re-entry programs are all time-honored methods for helping convicts reintegrate into normal American life. [23][24][25]

One successful example is the Texas Prison Entrepreneurship Program (PEP), a selective MBA-style educational program for inmates who demonstrate work ethic and a desire to take charge of their own lives.[26] Another is “Code.7370,” a 6-month program at San Quentin Prison which teaches eligible inmates how to develop websites.[27] Graduates of these programs have recidivism rates of only 7%![28]

Programs with no selection bias have also been highly successful. In Saskatoon, Canada a sexual offender treatment program used cognitive behavioral therapy to treat male sexual offenders between 1981 and 1996. In a comparison of 296 treated and 283 untreated offenders, only 14.5% of the treated group reoffended vs 33.2% in the control group.[29] In Hillsborough County, Florida, 18,000 domestic violence offenders were subjected to a tiered treatment program from 1995–2004. The program reduced domestic violence recidivism to 8.4% vs 21.2% in the control group.[30]

As these examples illustrate, the main challenge is not discovering what the best ideas are, it is crafting a market mechanism that rewards innovators for iterating on different holistic treatment regimes until they achieve the lowest possible recidivism rates. The fundamental problem with American criminal justice is not a lack of good ideas, it’s the system itself. We need to literally create a marketplace of ideas — a bottom-up, competitive arena in which the best ideas win. If we reward innovations which demonstrably reduce America’s prison population, bright entrepreneurs will deploy their talents to fix our broken prison system.

Regulators should supercharge this new competitive market by lowering regulatory barriers to entry, which will force CoreCivic and the GEO group to innovate just as intensely as their nimbler competitors. Relationships with state legislatures and regulatory bodies should not be enough for these giant corporations to win procurement contracts. In the medium-term, we hope that the industry will evolve to become more diverse and competitive. In the long-run, we envision a system where transparent, compassionate private prisons have become so successful at rehabilitation that they have replaced public prisons as the dominant mode of incarceration in the United States, and would continue to compete to successfully reintegrate former prisoners into their communities.

Though we’re excited by the prospects of rewiring the private prison market to solve America’s incarceration problem, we recognize that challenges for American criminal justice remain. In his seminal essay on the “prison-industrial complex”, Eric Schlosser wrote that we are fighting an establishment

…composed of politicians, both liberal and conservative, who have used the fear of crime to gain votes; impoverished rural areas where prisons have become a cornerstone of economic development; private companies that regard the roughly $35 billion spent each year on corrections not as a burden on American taxpayers but as a lucrative market; and government officials whose fiefdoms have expanded along with the inmate population.[31]

Dismantling this complex of special interests — which also includes prison guard unions and aggressive, careerist public prosecutors — will be difficult. Fortunately, prison reform is one of the few truly bipartisan issues in our nation today. Harnessing America’s brightest entrepreneurial talent to heal inmates and reduce recidivism could be a powerful antidote to America’s prison crisis.

Joe Lonsdale

Partner, 8VC