Joe Lonsdale, Founder of 8VC discusses jobs, universal base income, and inequality and many other dangerous topics with Sam Lessin.

Click here to listen to this podcast

|June 10, 2017

Joe Lonsdale, Founder of 8VC discusses jobs, universal base income, and inequality and many other dangerous topics with Sam Lessin.

Click here to listen to this podcast

|April 21, 2017

I am not by any means a philosopher although I have worked with some talented people in the discipline. But certain philosophical concepts deeply inform the way I think about the world. The idea of "opposing truths at extremes" is a powerful concept that I came to appreciate in my twenties.

My personality has sometimes been called a little intense. When I spend a lot of time reading, discussing, or thinking about an area, I'll often really appreciate why a strong viewpoint is true and come to very firm conclusions. But if I am later exposed to a strong opposing view I frequently find this countervailing view persuasive as well. I found this initially confusing. How could two extreme, contradictory viewpoints both be true?

One great thinker on this issue is G.W.F. Hegel:

The abstract thinking of the understanding is so far from being something firm and ultimate that it proves itself, on the contrary, to be a constant…overturning into its opposite, whereas the rational as such is rational precisely because it contains both of the opposites as ideal moments within itself.[1]

This is what I mean by a “dialectic”, where the truth exists at different extremes and the actual truth is a complex interaction between an initial understanding and its negation. The idea is that most polarizing viewpoints, whether practical or theoretical, contain within themselves apparent contradictions which seem to drive one to the opposite pole. But much as a Zen master appreciates both sides of a koan, one should strive to recognize that two contradicting extremes can often be simultaneously valid.

Many people are sloppy thinkers, and opt for “middle of the road” positions when faced with two opposing extremes. But compromise is often even less accurate than the extreme poles of a dialectic. In my experience, it's common that deep truths exist at both extremes of a dialectic, and the wisest stance on an issue will incorporate “both of the opposites within itself”.

Deeply understanding something and being a passionate advocate on one side of a debate (even in a way that may make others uncomfortable) is a great start, and the path to wisdom. But with maturity comes the insight that you should remain open to ideas and views totally incompatible with your own. I have learned that if I only see and deeply appreciate one side of an argument it means I am probably missing something important.

OK, that was a bit abstract. Let's go over some examples...

An obvious one is the product part of an organization. It's true that a great product team will collect lots of user feedback, systematize it, and make data-driven decisions – a “scientific” approach to product. However, as we know from Sony in the 1980's, Steve Jobs, and other iconic product organizations, it's also true that greatness in products requires leaders to tell customers what they want, not merely to ask and respond to customer data. This requires leaps of creative intuition, or an “artistic” approach to product.

These are conflicting methodologies, but extreme forms of both must exist inside of a product organization for it to be great. It's easy for experienced company-builders to see how mistakes will be made by only relying on one of these and not the other.

Another example is the dialectic between entrepreneurial vigor and lawyerly/bureaucratic restraint. As an entrepreneur, I had a strong bias to move quickly and decisively. I found it frustrating and suffocating when legal counsel or management restricted my freedom to experiment. I understood that most big corporations and government institutions function in massively inefficient ways (which created huge opportunities for Palantir and other ventures). Although I remain committed to these views, I have now grown to appreciate that a bunch of ardent entrepreneurs with large risk appetites can be too volatile; that you need corporate governance and procedural checks to keep a company from blowing up. What’s important to recognize here is that a company should not strive for a middling balance between these two extremes, it should cultivate both at once. Great executives understand that they need to incubate ambitious entrepreneurs with a bias towards fast iteration and “breaking things,” while ensuring that experienced leadership and legal personalities keep the company on a stable trajectory. It’s a very challenging paradigm to master.

A third example is the dialectic between breadth and depth. It has been my experience that deep, obsessive focus at the expense of other areas of life yields exponential returns. The curve tracking productive output against the time a person invests in a single subject matter is highly convex. Yet I have also come to realize the importance of building bridges and relationships across disciplines, and in equally vital pursuits such as family life. A fully torqued engine burns out more quickly. I have discovered that extra-disciplinary conversations spark my intuition and create important synergies for the businesses I have been a part of. My bias is to work extremely hard and dive very deeply into topics, and I attribute some of my greatest work (such as at Palantir and Addepar) to periods of extreme focus. But developing relationships with experts outside of my chosen fields and cultivating other personal interests has helped me expand my worldview and pinpoint opportunities I might have otherwise missed entirely.

These are a few examples for how I apply Hegel’s insight when thinking about startups, but of course dialectics surface nearly everywhere. One profound dialectic I have encountered is between what I’ll call “Nietzschean behavior” and “altruistic virtue.”

A very small proportion of human beings – perhaps the top 1% - has a wildly oversized impact on our political fate and the progress of our species. I am “inegalitarian” with respect to talent. I believe that a small cadre of industrialists, thinkers, artists, and statesmen dominate world affairs largely because of their natural talents and internal will to power – though sheer luck certainly plays a role as well. Effective leaders will understand how to learn from and leverage the extraordinary talents of elite members of society. Great leaders often live extremely uncommon lives, and Nietzsche points out that many elite leaders develop a “pathos of distance” from the affairs of the ordinary person. This remove may stimulate the severe self-criticism and “constant self-overcoming” which enhance a leader’s ability to impact and transform the world.[2] An effective leader will understand when to withdraw from normal life and apply herself to grand projects.

But while it’s true that talent is unequally distributed, a thoughtless, self-glorifying aristocracy is a very dangerous thing. Is it any surprise that Hitler and Mussolini displayed the cruelest forms of Nietzschean behavior – even drew directly upon Nietzsche as inspiration for their atrocities? I believe that truly great leaders are those who embrace the dialectical counterpoint of moral equality among persons, and cultivate a deep sense of altruistic virtue. I personally believe this egalitarianism finds powerful expression in Judeo-Christian principles: compassion for the meek, mercy, and love for thy neighbor as thyself. Powerful individuals often find themselves pulled in different directions by the forces of elitism and virtue, and in fact this is a healthy tension. Many great leaders have both a strong sense of exceptionalism and an unwavering moral compass.

To recap, I believe that wisdom is very often dialectical in nature. Extreme, conflicting viewpoints are often simultaneously true – whether in business or more broadly in human life. It is the hallmark of a wise individual to eschew the milquetoast path of middling compromise, and instead to embrace these “antinomies” of reason and fuse them into a concrete course of action; to be patient and comfortable with cognitive dissonance. I encourage young entrepreneurs, dreamers, and other visionaries to strive to explore both sides of every issue. Dialectical wisdom has been integral to my success and well-being.

[1] Hegel, G.W.F. “The Encyclopaedia Logic” Trans. T.F. Geraets, W.A. Suchting, and H.S. Harris. Hackett, 1991. p.133

[2] Nietzsche, Friedrich. “Beyond Good and Evil.” Trans. Judith Norman, Cambridge U.P., 2002. p.151

|April 12, 2017

“[With] the substitution of machinery for human labour…there will necessarily be a diminution in the demand for labour, population will become redundant, and the situation of the laboring classes will be that of distress and poverty.” – David Ricardo, 1817.[1]

An increasingly popular concern is that robots will eat up labor’s share of income at an accelerating rate, leaving ordinary workers impoverished and unemployed. A common topic at dinner conversations in Silicon Valley is universal basic income, and the typical argument advanced for UBI is that we are destined to indefinitely continue losing jobs faster than we replace them. Variants on this theme have circulated since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Improvements in farming technology have been greeted with skepticism since ancient times for these reasons. Mechanical contraptions for sewing and other tasks were decried as potentially ruinous to workers in Elizabethan England. Around the same time that working-class Luddite Rebellion and Captain Swing protestors rioted and destroyed machinery, upper class Victorians issued treatises on the bleak prospects for most workers.

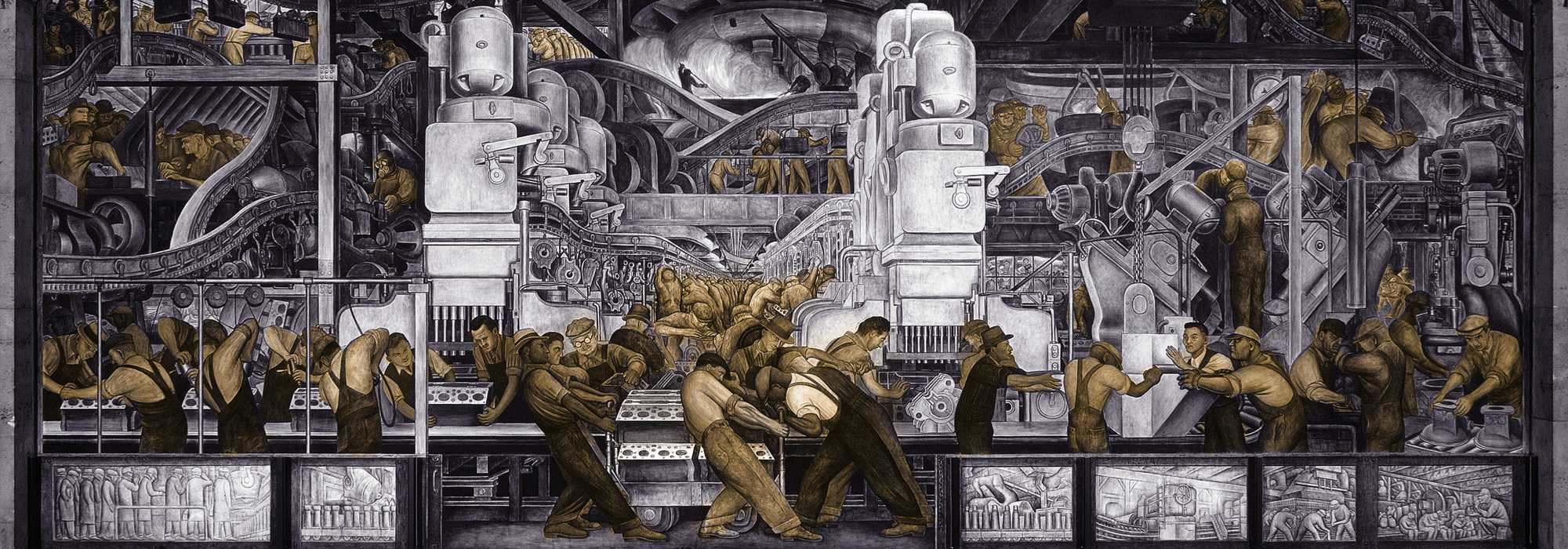

There is always a grain of truth to these complaints, because technological innovations inevitably displace some segment of the workforce. In general, the current technological revolution is displacing those workers whose jobs consisted of routine, repeatable tasks. The information architecture underpinning the work processes of all our major industries is being upgraded to cloud and mobile ecosystems and is leveraging big data in thousands of new ways – a trend we describe in The Smart Enterprise Wave. One consequence is that many cashier, telephone operator, mailroom, clerical, stenographic, and data-entry jobs are on the way out. In addition, advances in machine learning and robotics make it possible for manufacturers to accomplish more with fewer workers. We may also experience temporarily higher unemployment as semi-autonomous vehicle technology enables a pair of truck drivers to safely navigate a convoy of multiple trucks. Roughly 50% of jobs in the US economy have been replaced with new forms of labor every 60-90 years.[2]

Technological unemployment is always scary because it’s hard to understand what the future will hold – but despite spikes during brief periods of disruption, unemployment rates have not appreciated over the course of the last three centuries. Innovation is the only sustainable way to make society wealthier and better-off. In terms of real GDP, Americans are on average more than 8 times wealthier today than they were in 1917[3]. In the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth was practically the only person wearing silk stockings. In the 21st century, any American woman can. A similar point holds true for cars, plumbing, electricity, and a variety of other modern wonders that began as luxury goods. When technological unemployment occurs, laid-off workers seek retraining and private sector leaders create transitional infrastructure to reabsorb them into the economy. Innovative technologies create more wealth and better jobs in the end by eliminating unpleasant rote work and increasing overall productivity.

In the past 30 years we have experienced a complicated period of globalization. Global inequality has actually decreased as emerging markets have prospered from market reforms. However with global competition, prosperity in the West has been unequally distributed – many working class families have struggled in the face of stagnant wages. But we should not lose sight of the positive 100-year trend of rising standards of living for all demographics of American society.

Imagine that you are an average American living in the late 19th century: a time when workplace fatalities were 30 times more likely than current levels, there were rampant disease outbreaks of typhoid, cholera, and tuberculosis, and many farmers were barely able to sell enough crops to survive. Even if you were a wealthy, talented visionary, you still wouldn’t have been able to imagine the new kinds jobs that would be available by the 1980s. If a time traveler attempted to explain the concept of MTV, a Best Buy, or an air traffic controller to you, you would have been completely lost. You would have been justifiably worried about the future unemployment of the bobbin turners, candle makers, and small-time agrarians of your day. But hundreds of millions of new employment opportunities would open up, as living conditions continued to surge upwards. Neo-Luddite fears about technological unemployment are limited in the same way as our ancestors’ worldviews. The late 19th century was not the end of history, nor is today. Innovation has consistently led to greater productivity - meaning society can produce more with less - and an increased demand for new jobs and services. To avoid the Luddite mistake, we must think about the future of labor with a healthy dose of creativity and an expansive frame of mind.

---

The “creative destruction” driven by innovation is scary because it’s hard to predict what a future, wealthier society looks like. Imagine explaining software engineering to your great, great grandparents! Here are twelve example ideas for areas where we might expect future jobs.

Hollywood and gaming industries will collaborate to create customizable virtual realities populated with avatars based on real-life actors and tailored to your specific preferences.

Advances in “foglet” technology will allow individuals to direct their surroundings to change in shape and tone by reordering nanoparticles in a room – customizing their homes at will.

Baby boomer retirements will create a wave of demand for senior-care services which treat our elderly with the attention, compassion, and respect they deserve

As psychometric computing becomes exponentially easier, new jobs will emerge. Coaches able to track your emotional state with quantitative precision may be able to give you specific feedback on how to be happier, more logical, how to avoid certain classes of cognitive mistakes, or maybe even how to be more ethical.

We are only scratching the surface of what it’s possible to build with synthetic biology. Imagine landscapers working with exotic alien flora, or children growing up with minatiurized hippo pets who become happier when the children study hard! With developments in plant modification we may be able to create super-vegetation that curbs global warming, cures common ailments, or even just complements a favorite varietal of wine particularly well.

---

But Doesn’t AI Destroy All Jobs?

Many of our friends believe that we are on the brink of developing superhuman artificial intelligence which will replace human labor, radically transforming our productivity function. Views that AI poses a serious existential threat or constitutes an incomprehensible inflection point in the history of our species have taken on the character of a religion in Silicon Valley. While post-humanism is a fascinating obsession, and many take for granted the notion that computers will soon exceed human beings at nearly everything, I believe that the singularity is much farther away than people imagine. Machine learning is slowly improving and impacting many important industries, but is nowhere near the level of general human ability. If we all merge into a godlike super-consciousness or face events of similarly biblical proportion, concerns about employment will pale in comparison to more fundamental questions about the meaning of existence. But although some in every generation are eager to believe that a version of the messiah is soon to arrive, it is much more likely that in the meantime history will continue to unfold according to the economic logic of innovation, creative destruction, and job growth we saw in the 20th century.

While some view AI as a kind of salvation, others have responded with anxiety. Policy rooted in fear tends to be irrational and repressive. The pro-jobs response to disruptive innovation is to cultivate a flexible economy that can swiftly adapt to technological change. First, we should increase upward mobility by making it easier to move and participate in high growth economic areas. This means fighting NIMBYism and poor zoning laws, and developing more suburbs in inexpensive areas 100-300 miles outside of our top cities. It also means introducing faster modes of transportation which enable people to live nearby and commute. Deployed with tunnels where necessary, the Hyperloop, for instance, would make it possible for millions of people to live in inexpensive areas but access upward mobility in metropolitan centers. Second, we should make it easier for entrepreneurs to start new firms and employ more people in new forms of work. Wealth is only ever actually created from the bottom-up, with free people employing their distinctly human creativity and finding ways to serve and employ others. To make sure we're creating new jobs we need to cut the red-tape of over one million rules that make our economy sclerotic and deter new business formation - and allow the market to rapidly evolve on its own terms to find new ways of employing millions of people.

Fear is the wrong response to technological unemployment. Focusing on economic flexibility and adaptability - with special attention to eliminating the barriers we've accidentally created to the mobility of the working classes - is the right response to technological disruption. With sound policy in the context of a free and open society, I am optimistic that the coming advances in AI will massively reduce the cost to live a good life, and increase wealth and opportunity for all.

Technological unemployment is scary for those affected – but has always gone hand in hand with economic progress. In the next few decades we will continue to invent new ways to entertain, educate, serve and delight others, employing billions in the process. Populists will predictably vilify innovation - fear and hatred are powerful political weapons. But as our society grows more prosperous in absolute terms, raising the bar on the very definition of poverty, we will continue to create opportunities for people from all walks of life. The human mind and body remains the most complex, powerful machine on the planet, and we will adapt and thrive in a world of accelerating technological change. We owe it to our grandchildren to continue innovating.

[1] Ricardo, David. “Principles of Political Economy and Taxation,” 1817. Chapter 31. http://www.econlib.org/library/Ricardo/ricP7.html#Ch.31, On Machinery

[2] See: Wyatt, Ian D. and Daniel E. Hecker. “Occupational Changes During the 20th Century.” Monthly Labor Review, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2006. https://www.bls.gov/mlr/2006/03/art3full.pdf.

[3] Jones, Charles I. “The Facts of Economic Growth.” Stanford GSB and NBER, December 2015. p. 2 http://web.stanford.edu/~chadj/facts.pdf

|January 31, 2017

“By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food until you return to the ground, since from it you were taken; for dust you are and to dust you will return.” — (Genesis 2:15)

In 1930 the economist John Maynard Keynes wrote a short, influential essay entitled Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. The Depression had not yet hit rock bottom, but Keynes was worried about a macroeconomic trend he called “technological unemployment” — namely, “unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour.”[1] Automation anxiety is an ancient phenomenon, and includes a lineage of distinguished British thinkers dating back to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. In the following decades, Keynes’ essay became the focal point of a large literature on the idea that machines will create widespread structural unemployment.

Today, we are likely in the very early innings of another major wave of innovation and technological unemployment.For this reason, it is useful to think about what Keynes got right and wrong.

Keynes projected that 100 years hence, the standard of life in Western countries would approach 8 times the level it was in 1930. His prediction was remarkably accurate. Since 1930 GDP per capita in the US has increased 6.5x, and should hit 7.5x by 2030.[2] Keynes thought this enormous increase of wealth would gradually liberate human beings from the necessity of working at all — but he had drawn the wrong implications from his economic data. The great thinker predicted that in the superabundant 21st century “three hours a day” would be enough to satisfy most people. But for the average American the number remains close to eight.[3]

The explanation for this discrepancy is that in the past hundred years we have found myriad ways for wealth to raise our standard of living. Any living American feels “poor” if he lacks access to inventions such as cars, indoor plumbing, and modern medicine. We adapt to technological progress by raising our minimum standards of living and working to stay above this rising threshold. Consequently, the cost not to be “poor” today is higher than it was in Keynes’ time. There are still at least hundreds of years of progress to be made in science, medicine, and technology. There are new corners of the human psyche to be explored with the tools of psychology and neuroscience, transportation systems and metropolitan infrastructure to be reengineered, and advancements to be made in literacy, numeracy, and sanitation. We have yet to fully explore depths of the ocean floor or the other planets in our solar system. As we progress as a species, we will unlock new means for enhancing our lives at every turn — and our conceptions of wealth and poverty will evolve in tandem.

Technological innovation will empower us to live lives of plenty. But it is not in our nature to pursue lives of leisure. Critics of capitalism often describe work-ethic in terms of greed and unending materialism. They ask: what reason do we have to continue working hard once our biological needs are met? The answer is that work is in fact profoundly positive-sum. Hard work enables us to improve ourselves and the world around us, to combat injustice, reduce suffering, and increase human freedom. It allows us to live out the principles of progress, humaneness, and service to others known as “Tikkun Olam” in the Jewish tradition. Hard work makes us better people and helps our communities flourish.

Keynes’ fundamental error is to conceive of work as purely instrumental to a good life. He argues that technology will ultimately solve the “economic problem” of providing for our basic biological needs, thus freeing us of any obligations to work at all. In Keynes’ post-economic utopia supply and demand will dissolve away — much as they do in the aftermath of Karl Marx’s “proletariat revolution.” In a world where labor is automated and capital resources are widely available, “it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.” Keynes is careful to note that this future will take a long time to materialize, writing that our work ethic and “intense purposiveness” will remain strong within us for many generations. But ultimately labor will go the way of the lamplighter and we will be left to pursue the art of life in days of complete leisure.

To really get to the bottom of Keynes’ essay, you need to understand his taxonomy of biological needs. Keynes thinks human needs are twofold. He claims that we feel “absolute needs” — preconditions for biological survival and psychic stability — regardless of the circumstances of our fellow human beings. We also feel “relative needs” to be superior to other human beings…what Hegel called the “dialectic of lordship and bondage”.[4] Although our cravings for relative status are infinite and insatiable, our absolute needs have natural limits — adequate shelter and food supply, companionship, and possibly entertainment. For Keynes the “economic problem” consists in adequately covering these basic needs for the entire human population. He writes, “We have been expressly evolved by nature — with all our impulses and deepest instincts — for the purpose of solving the economic problem.”

Unlike Keynes we think that our needs are mostly relative in principle. The human outlook is deeply grooved with assumptions of scarcity at the level of the human genome. From the perspective of evolutionary biology we are wired to assume that calories, sexual reproduction, bodily security and companionship are scarce goods. Keynes’ taxonomy of relative and absolute needs isn’t useful in thinking about genetic determinants on human behavior, because from the perspective of the gene all of our desires are limitless. It is a wonder that this idea was lost on Keynes, who famously described market decisions as the result of spontaneous urges in the form of “animal spirits”! Instead, there are infinitely many ways in which we can improve our societies, as befits our finite, corporeal nature.

There is always something to fix, improve, create or amplify. Therefore, labor is not a zero-sum game of working the precise amount necessary to satisfy a limited set of natural desires for food, shelter, security and community. If it were, most of the Western world, staggeringly wealthy by historical standards, would surely have stopped working hard in the early 1900s. The distinction between the “developed” and the “developing” worlds is a false dichotomy — the difference is not a matter of kind but of degree. We are all developing towards a more prosperous future. In other words, Keynes’ “economic problem” should be recast as a perennial challenge: how can we improve our circumstances on earth today? While Keynes gets the evolutionary story partly right, he draws the wrong philosophical implications.

“Temporary spates of technological unemployment will be followed by golden eras of human liberation.”

We intrinsically crave heightened sensual experience, superior physical health, a richer understanding of our world, and elevated artistic achievement — as well as more extensive peace, prosperity and justice for our fellow man. It is in our nature to continue to climb. This drive has gone by different names in different times; for the Platonists it amounted to a telos of divinity, for Nietzsche it was a secular “will to power.”[5] Buddhist and Stoic traditions counsel a repudiation of these earthly drives — and there is much to say for a wisdom of detachment. But for those who choose to remain engaged in the world, hard work is a clear path to human flourishing. It is no surprise that great thinkers have often commented on the way in which meaningful work determines a person’s self-respect. John Rawls, for instance, argued that the lack “of the opportunity for meaningful work and occupation is destructive not only of citizens’ self-respect, but of their sense that they are members of society and not simply caught in it.”[6] Work empowers us not only to survive, but also to thrive; to improve the lives of others by inventing new solutions to social problems even as our own lives are enhanced by others’ creativity.

Keynes’ “needs-satisfaction” paradigm is an impoverished way of thinking about our place in the world. Levels of humanitarian engagement with developing countries are soaring in Europe and the United States, even as we work to improve our own societies. We are creating new and more varied forms of art, cuisine, and entertainment as technology and wealth free up people to exercise their creative ability and help others. Keynes’ mistake was to miss the unbounded spirit of progress animating these developments. There is much more we can do to improve the condition of humanity, at home and abroad. Over the course of the next century, technology will lift most people out of poverty as-currently-defined, satisfying the material needs of the global population in creative and more efficient ways. We shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that true poverty in 1916 was far worse than most “poverty” in the 21st century. If we are able to maintain a society which holds fast to the Western tradition of markets and property rights, we will continue to foster innovation and economic progress.

In the coming years, new jobs will be created in industries that require the cognitive skills of creativity and intense analytical reasoning, as well as in areas where human contact is at a premium. We will see an explosion of jobs in health and senior care, professional coaching of all kinds, e-marketing, and an expansion of executive assistant and chief of staff roles catering to the needs of our swelling upper-middle class. The mechanization of rote tasks will allow Americans to focus on the distinctly human advantages of complex sensorimotor skills, social intelligence, and lateral thinking. Work in the 21st century will be more fulfilling for Americans than the manual labor and “human middleware” jobs that characterized the last half of the 20th century. Temporary spates of technological unemployment will be followed by golden eras of human liberation in which we channel our talents towards improving our society in unforeseen ways.

There is much to be said for Keynes’ vision of the world. His macroeconomic calculations were startlingly accurate, and we admire his optimism about the possibility of creating conditions in which all human beings can live healthy, meaningful lives. He was correct to identify technological unemployment as a true social problem. But in conclusion we would do well to remember that Keynes’ central view in Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren has not withstood the test of time. We are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Keynes’ generation. Yet here in the 21st century — several factors wealthier than Keynes’ generation in real terms — we are more fully ingrained in a global economic order than ever. We believe that as the automation of old jobs continues, people will find new and exciting ways to employ their distinctly human faculties. In the spirit of progress, we will continue to transform the world around us into a more beautiful, plentiful, and empowering place. Only in so doing will we cultivate the art of life to its most vibrant expression.

This is the first installment in a two part series.Here we unpack the philosophical and evolutionary assumptions at work in the debate over technological unemployment. In Future of Labor II, we discuss the economics of new job creation and chart several industries of the future which will create employment opportunities for American workers. Future of Labor II was published by WIRED and can be read here.

Is the end of labor nigh? Here are a few well-known philosophers and economists who all mistakenly thought so:

“The servant is himself an instrument which takes precedence of all other instruments. For if every instrument could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the statues of Daedalus, or the tripods of Hephaestus, which, says the poet, ‘of their own accord entered the assembly of the Gods’; if, in like manner, the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, chief workmen would not want servants, nor masters slaves.”

Under these circumstances the following proposal may be offered to our consideration namely, that since the price of a manufacture depends so much on the wages paid, and the numbers employed in making it, so consequently the fewer that shall be employed about it, the cheaper will be the manufacture: no in order to complete a work by few hands, engines and machines are contrived to supply the place of a greater number…here it may seem strange that in a discourse concerning the benefit of employing our people, a recommendation should be offered of that which must destroy the necessity of their labour: all that can be alleged in answer to this is that since other nations do make use of such engines and are thereby enabled to offer their productions at a low rate, it is in vain for us to preserver in toilsome methods.”

“But the machines I never wish to see introduced into a commercial nation, (which is required to be fully peopled, that is, to have a sufficient number of hands for all the classes of life already described) are saw-mills, and inventions of that stamp, which are calculated to exclude the labour of thousands of the human race, who are usefully employed in dock-yards, in those of timber-merchants, private ship, and house-builders, cabinet-makers, etc. A more pernicious scheme could not be devised…It is possible there may be counties in England where one such machine might be wanted, from the scarcity of hands for other branches; but surely every other expedient should have been first tried…”

“Population, nevertheless, increases the supply of labour in at least as great a ratio as the demand existing under a restrictive system. Every invention, therefore, which diminishes the quantity of labour necessary to produce the objects of barter, lessens its price, and excludes, for an indefinite period, a great part of the population from employment. By this system the profits of capital are increased, though not in the same ratio as the wages of labour are for a time diminished.”

“I am convinced that the substitution of machinery for human labour is often very injurious to the interests of the class of labourers…the same cause which may increase the net revenue of the country, may at the same time render the population redundant and deteriorate the condition of the labourer…as the power of supporting a population, and employing labour, depends always on the gross produce of a nation, and not on its net produce, there will necessarily be a diminution in the demand for labour, population will become redundant, and the situation of the laboring classes will be that of distress and poverty…the opinion entertained by the laboring class, that the employment of machinery is frequently detrimental to their interests, is not founded on prejudice and error, but is conformable to the correct principles of political economy.”

“Capital advances the worker the wages which the latter exchanges for products necessary for his consumption. The money he obtains has this power only because others are working alongside him at the same time; and capital can give him claims on alien labour, in the form of money, only because it has appropriated his own labor. This exchange of one’s own labour with alien labour appears here not as mediated and determined by the simultaneous existence of the labour of others, but rather by the advance which capital makes. The worker’s ability to engage in the exchange of substances necessary for his consumption during production appears as due to an attribute of part of circulating capital which is paid to the worker, and of circulating capital generally. It appears not as an exchange of substances between the simultaneous labour powers, but as the metabolism of capital; as the existence of circulating capital…capital here — quite unintentionally — reduces human labour, expenditure of energy, to a minimum. This will redound to the benefit of emancipated labour, and is the condition of his emancipation.”

Joe Lonsdale

General Partner, 8VC

[1] Keynes, John Maynard. “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.” 1930.

[2] Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce. “Table 7.1: Selected Per Capita Product and Income Series in Current and Chained Dollars.” 2015 data.

[3] Bureau of Labor Statistics. “American Time Use Survey Summary.” 2015. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.nr0.htm

[4] Hegel, G.W.F. “Phenomenology of Spirit.” Trans. A.V. Miller, Oxford U.P., 1977 [1807].

[5] Nietzsche, Friedrich. “On the Genealogy of Morals.” Ed. Walter Kaufmann. Trans. Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale. New York: Vintage Books, 1989. Section 1.13

[6] Rawls, John. “The Law of Peoples: With, The Idea of Public Reason Revisited.” Harvard U.P., 1999.

|December 13, 2016

“The graveyards are full of indispensable men!” — attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte

In his eponymous autobiography, Michael Bloomberg wrote:

I want the loss of anyone in the company to hurt us, but not fatally, including the likes of me. Every job performance review I give my direct-reporting managers includes the question, ‘Who’s your replacement? If you don’t have one now, I can’t consider you for bigger things. If you don’t have one the next time I ask, you may no longer be a direct report.

One of the most important jobs of a great leader is to attract great talent. How adaptable you are as a firm depends in part upon how your company is organized, but most of all it depends upon the people operating it. Internal leaders are sometimes secretly afraid to bring in ultra-talented employees because they fear that these newcomers could challenge their status at the firm. A talented executive whose interests are aligned with the firm’s and is confident in her role will always recruit stars who exceed herself in various ways, but one who is worried about her value to the firm will not.

A great leader should make it clear to her team members that as a matter of culture her job is to replace herself. A new hire should know from the outset that she will ultimately have to bring in new talent to replace herself so that she can personally better herself and achieve loftier goals. A policy of knowing your replacement is one of the best ways to drive a growth culture. It anticipates and eliminates the most harmful politics in leadership for an expanding company, and instantly sets the right tone for a high talent, growth mindset executive team.

Moreover, to craft a truly durable company you have to plan for as many contingencies as possible. Many contingencies are all-too-human variables: injuries, illnesses, changes-of-plans, early retirements and so on. Vacancies in your company’s structure are essentially unpredictable, and can be very costly. The departure of key individuals kills morale, loyalty and productivity among your employees. Great leaders are paranoid by nature and always plan for contingencies. They always ask: “Where are the bottlenecks? Which people can I not afford to lose?”

Questions of management depth extend beyond hardship and transfer cases. For any rapidly growing company vacancies will be a recurring problem. Scaling up typically means hiring new employees to fill lower-level positions as your more experienced team members graduate into more senior roles…although it may also require you to introduce experienced executives directly.

On a personal note, I have always been of the mindset that my most talented friends and colleagues are the critical ingredient in my success. I’ve been proud of my entrepreneurial roles as a leader and builder of company culture, head of product, head of BD, or CEO of some companies I’ve helped to found such as Palantir and Addepar. However, I’ve been lucky to have consistently replaced myself with very talented colleagues in the specific areas needed by our companies. Usually when this occurs I begin building in other areas, or my replacements choose to keep me around to help out with mentorship, strategy, or fundraising in various ways — although some of them are perfectly happy without somebody looking over their shoulder and taking credit for their work! This has helped me expand the range of projects I can channel my energy into, attract an ecosystem of brilliant, talented individuals and foster growth cultures at the companies I have been a part of.

In order for a company to grow, its team members must grow themselves — and this means personal evolution into new roles and more ambitious assignments. We admire Bloomberg’s clarity of thought, and his success as a leader suggests we should pay closer attention when he shares this kind of wisdom.

So, who’s your replacement?

Joe Lonsdale

General Partner, 8VC

|December 4, 2016

We recently put together a speech outlining the major functions of a modern Venture Capitalist. These notes from the speech articulate our basic framework for thinking about the shifting nature of the Venture Capital industry.

The Venture Capital industry currently manages about 100x what it did 30 years ago. As our industry has grown, it has evolved. The role of a modern VC has become substantially more nuanced and multifaceted than VCs of the 1970s and 1980s could have ever predicted. Today, many top Venture Capitalists are people who have started companies themselves. Venture Capitalists play a positive sum role in helping investors create value by partnering with entrepreneurs and give them every advantage possible to beat the odds and succeed. For many of us as VCs, it’s exciting to help instantiate new ideas for platforms and processes which improve how people live or how industries function. We’re eager to leverage our own experiences and networks to help entrepreneurs however we can, and continue to learn as we work on new projects.

The roles of the modern VC can be summarized as finance, community, and leadership.

As a financier, a Venture Capitalist might be:

(1) A Middleman. Wasteful Middlemen are what we like to call “New York Fabulous!” A sophisticated middleman will raise and allocate capital in a way that benefits society as a whole, rather than focusing on short term profits .

(2) An Expert at Structuring and Closing Deals. A VC must ensure that deals involve fair terms with no trickery as well as assigning the correct valuation to a prospective company. Deals must align the interests of parties involved so that they are mutually protected. This also applies to how a VC structures its fund vehicles.

(3) Macro Analysis Investor. This is the more interesting part of finance! VCs must understand historic technology waves as well as predict emerging waves. We think that bioinformatics, smart enterprise, and transportation are three of the most important emerging technology waves as we head into 2017.

As a community builder, a Venture Capitalist might be:

(4) A savvy Network Connector for sales, customer feedback, and business development. A great VC network includes Sales, Customer Service, Business Development, and Channel Partners.

(5) A Talent Resource for hiring. VCs help portfolio companies hire top talent, and need to be able to help companies attract the right engineers, designers, sales superstars, executives, and board members.

(6) A Brand Creator for company and firm. Good brand creation is about building a trusted, respected community around your portfolio companies, which includes customer relevant networks, advisors, talent, internal operations, and your general brand. The involvement of a top VC is an important symbol for everyone around a startup — other investors, employees, potential partners and clientele. Today, the most impactful brands inside the technology world are created more with substance and success than through media. And clearly, this skill is related to a VC’s ability to build a relevant community achieve numbers four and five above for the company, as well.

As a leader, a VC might be:

(7) A Technology Consultant. In addition to providing financial support, today’s VC needs to be able to counsel portfolio companies on elements of data science, tech architecture, and design thinking. Some VCs should be fonts of advice on product or technology. Scaling a technology presents some of the hardest technical challenges for a growing company.

(8) Leadership, Management, and Strategy Mentor. Venture Capitalists serve an advisory role to budding CEOs. Top entrepreneurs are great engineers, but often not yet great leaders. Good VCs will teach entrepreneurs how to delegate authority efficiently and effectively, as well as how to scale a company. VCs who have been entrepreneurs themselves will be able to draw on their experiences to give budding CEOs specific, immediate feedback — creating value for all parties involved.

In the speech we put together — where each of these categories is a series of slides — we emphasize that not every VC plays all of these roles. Some specialize in certain areas, or have uniquely talented partners that complement each other well. But the bar has been raised and continues to climb, as investors with relevant experience and skills help startups across the board partner with leading entrepreneurs and create value. It’s amazing how this system has evolved and improved upon itself over the past decades through human ingenuity and market forces, and we are very bullish on many aspects of the top of the Silicon Valley ecosystem.