Lately I’ve had a strong sense that we’re living at a particularly important time in history, and I feel really lucky to get be able to interact with a lot of the actors firsthand.

It always struck me as pretty cool that people who changed the world often knew each other. After reading them separately, hearing that David Hume and Adam Smith were friends made sense. And after studying world champion Emanuel Lasker’s games as a young chess player, it was fun to find out he was close with Einstein. Lasker, of course, was the better player — chess, like many great skills, is helped along by genius, but without exception seems to require thousands of hours of intense study and perseverance to reach the highest levels.

It is particularly amazing that Cato, Caesar, Virgil, Ovid, Horace, and Livy were all speaking, writing and interacting at one time. These and other contemporaries were each studied for hundreds of years afterwards by every Roman schoolboy, and even into our day shape more of our culture than we realize. And when I was younger, I just assumed that their Greek predecessors Socrates, Plato and Aristotle had lived within a general period and been the most influential thinkers of a civilization — I didn’t realize that each had taught the next as their top pupil. Or that Aristotle then mentored Alexander the Great! Of course, these are just a few examples; others might include the pan-European Renaissance and the industrial revolutions and a variety of artistic and cultural movements, and no doubt many periods I am leaving out with my Western bias.

I’m not familiar with too much work on the topic, other than perhaps Charles Murray who has studied major centers of world-changing innovation and creation in “Human Accomplishment”. But it’s clear that something comes together and enables a culture and an energy at a certain place at a certain time to thrive in an amazing way.

We’re not claiming that any of my friends have reached the status of these legends, but it’s obvious to me we are living at one of these times. And if you see name dropping when I mention ideas, I hope you will forgive me — the goal is to give credit where it is due, and also to show off and document the ecosystem in which we are playing and building.

Lessons of Success

At a dinner last week with some of our CEOs, Henry Kravis of KKR continually referred to the importance of internal culture when asked about his success over nearly four decades and what he focuses on. Alex Karp at Palantir mentions this a lot, too — our view at Palantir was that as long as we can keep the internal culture strong and keep attracting the best people in the world, we can achieve anything and everything else will pretty much work itself out. But keeping internal culture strong is really, really hard. One of these two men discussed having to trim the leadership team every once in awhile over the years as part of this. And they each have a lot to do with their organizations’ culture with the strong and inspiring personal examples they set as leaders.

Success gives you a platform for further success — suddenly everybody wants to work with you, and your opportunities and possibilities open up. But at the same time, success is also immensely challenging — it ultimately often creates pride, stubbornness, and sloppiness that beget failure, taking down people and organizations. The consistently successful people I have met are aware of this and seem to think about it a lot. Our ancient Greeks above liked to say that the gods pile more and more pride on you, the more successful you are, until ultimately as a mortal it destroys you; the warning is that none of us can fully escape this paradox (but one might argue that it’s very helpful to be aware of it, and to fight it).

My favorite historical story of success becoming a blockade to more success was with Alexander the Great and his troops. I don’t know if it’s apocryphal, but apparently by the time they got to India, each of the troops had multiple servants — hairdressers and concubines and what not — and weren’t particularly interested in fighting anymore. They had enough and were enjoying their life, Alexander’s glory be damned. He knew he could not convince them to keep going. One even wonders if this secretly had to do with the great man’s early and untimely death. The joke at dinner was that this dynamic the troops faced was also a problem in NY, and could soon be one in SV as well. It’s something more of the leaders start to think about, as for example early employees ask to sell a small part of their shares and take ~25 million off the table at Uber, and Goldman Sachs strategizes with Travis about structures to enable this without destroying the culture. We definitely see ATG’s problem recurring in real time, and it becomes a counterpoint and a challenge to the focused, hard-working, substantive culture of SV. Success is not a challenge to be taken lightly for any part of our culture, and we have a lot to learn from each other’s experience.

This is how we do it at Apple

The problem of success pops up in a lot of areas, but one that I’ve struggled with a lot lately has been “successful” companies who are extremely stubborn about what makes them successful.

This is a two-sided issue. On one hand, a company is often winning because it’s the best in the world at something, and you don’t want to risk breaking that special culture and process that makes them the very best. On the other hand, the company may have just been doing a couple things right and then a few other things in really stupid ways that were never optimal but they won anyway, and now they are still being stubborn about the parts that are stupid and they aren’t willing to fix them or learn from others. This happens a lot. As David Sacks put it at a board meeting this week, whatever they were doing when they hit product-market fit gets enshrined and becomes untouchable.

This isn’t just a problem at my most successful portfolio companies. When my friend’s company was bought only a few years ago, she was shocked to find out that some of her colleagues at Apple didn’t know what A/B testing was, and that they didn’t have an analytics framework on the software side. Steve Jobs was a genius; he figured out what the customers wanted, designed it intuitively, and iterated on it. That was how it was done! A/B testing? That’s not what we do here. Of course, when are you running a lot of software projects, there is a dialectic, and great design is key, but an analytics framework is also important — it informs your decision making and teaches you what users are doing, where they are frustrated or unhappy, and where they are / are not taking certain actions. It’s just how it is done. Eventually, she convinced them to learn this best practice from SV and changed the process in this area.

Palantir, Addepar, Google, FB, Salesforce — everybody faces this problem. Salesforce was extremely stubborn about its web interface through the cloud, to the point where it was in danger and had to scramble to adjust to the new mobile realities. And now it’s not clear that it’ll be able to shift from single to multi-tenant for new data applications. Was hiring all these huge numbers of researchers and CS PhDs core to what made Google successful? Maybe. It certainly became enshrined into an obsession after their product-market fit. Palantir still has a very strong bias towards everybody being technical and maintaining an engineer-is-king culture, and keeping out others. Technical people own customer relationships and Palantir has eschewed regular sales — it is very stubborn about a lot of the practices that have been in place during its really fast growth in the last years. Alex Karp and the team are probably right about what outsiders don’t realize — it is really easy to destroy the innovative culture with less substantive and more political business people, and that it’s a complex and delicate balance between maintaining a strong engineering culture and expanding as a business. But of course, there are a lot of lessons to be learned from best practices at other firms too, and there are lots of areas where I think Palantir could learn from outsiders. They could hire more great writers and top PR people for more intelligent engagement with the press, and they could possibly invest in business process optimizations such as support departments for more established deployments — and many other things that everybody else does. That said, as the company scales, they’re figuring it out in a way that works for them — all of these firms are right to be slow and careful about what makes them unique, and to fight to keep their core culture.

But in general, companies very often become stubborn and point to their success and assume that whatever they were doing that was weird and quirky is part of their success. Another of our fund’s most successful companies has refused to build out certain traditional parts of its executive team, and generally will schedule meetings with important people and then cancel them multiple times in a row, often last minute, because they need to focus on their core business and metrics and they are having a busy week. And they are probably right to be ruthlessly focused, and right that certain executives they tried to hire were a distraction to the core value they were creating. Which doesn’t mean that, as a huge business, they don’t need to surround themselves with awesome people who can handle the issues that come with being a larger business, even as they continue to keep their core ruthlessly focused.

The question is how to take a successful company and learn from outsiders and keep challenging yourself to improve — and to do that without giving up your own special and unique identity. The rumor is that Theranos has fallen on this extreme as well, and is ruthlessly negative about the rest of SV and assumes it can learn nothing from its peers — and now that it has had early success and is lauded by the press, that quirk has become enshrined; none of us know them well. This happens a lot. Some firms will bring in traditional business leaders and lose their soul, which is the wrong extreme. But I think the overriding lesson is that the success often makes us arrogant and insular, and we should challenge our leaders to fight this. The lesson of history is to be proud and strong in your own view, but also to engage and learn from the other great people around you.

Operational Debt

I was speaking about the above with David Sacks at a board meeting for Addepar this week — he is one of the more thoughtful operational leaders in our space (COO PayPal, CEO Yammer, now COO Zenefits). He said he’s been thinking a lot about the idea of operational debt, which he believes companies incur just as they do technical debt when they grow quickly. You can’t always engineer all the right processes, just as you can’t build all the right long-term tech infrastructure, so you have a lot of operational hacks and inefficient structures in place to try to deal with things however you can as a company grows quickly. And your job is to be constantly fixing it and paying back some of the debt when you can amidst the madness of a hypergrowth company. Examples of this include a lot of things, such as how you build and handle various aspects of the customer life cycle — from marketing to sales to time-to-value to customer success/support and customer advocacy — to how you on-board employees and maintain internal culture. If resources aren’t available or processes haven’t had time to get built out, you just deal with it however you can, often by internal leaders filling in the gaps manually and in one-off ways.

(Other common examples of this are that a certain percent of sold clients aren’t qualified correctly and end up needing a ton of hand-holding by support to get value out of the product; deployment people having to do data integration by hand because there was no time to build the tools or materials to teach the clients; the CEO having to call or visit huge numbers of early clients in person because the relationships haven’t been passed off to an acceptable other senior person; marketing and product teams not strategizing or working in sync and having to revise materials and plans as the other groups’ plans change; etc. — there are hundreds of processes to get right).

The danger of course is to make sure to keep learning and to see what’s working well for what it is, and what is an operational hack that needs to be fixed (despite all the success you are having). Leaders are right to be paranoid — it’s really hard to figure out what really is your super-power and what actions are critical to the identity of your company. It may be really important not to follow a legal best practice that larger firms use, because it might destroy your firm’s entrepreneurial spirit if the lawyers infect the culture. Or maybe you are just being stubborn and don’t like dealing with a few lawyers, but it’s not that bad if you set it up right. This is where that old-fashioned wisdom about knowing yourself first before you can conquer the world really comes into play.

Are you Long or Short Innovation?

One of our fund’s core theses is about the smart enterprise platforms we believe will be created and drive a lot of innovation / capture a lot of value in major global industries in the coming years.

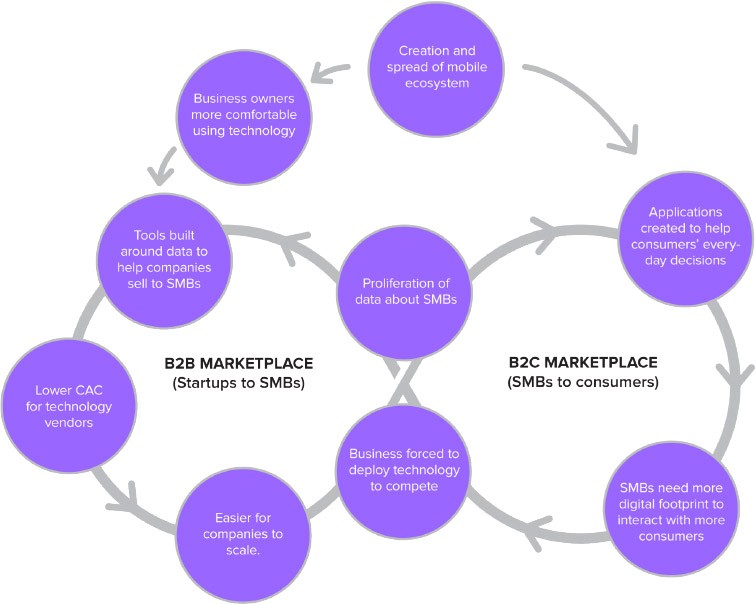

This is tied to our view of the world proceeding mostly in S-curves. When a new paradigm emerges, like the web, it first has a period where it gains some traction, and then a period of exponential mass adoption, and then finally a period where things stay basically the same for a while until the next paradigm emerges. As you progress through time, you see innovation going up in a bunch of S-shapes. Human history has seen several paradigms that define the information processes of their age. Beginning with the development of spoken language a hundred thousand years ago, and then the invention of written language five thousand years ago, discontinuous innovations have fundamentally changed the way that information flows through organizations and through society. In more modern times, paradigms that have come to define the information workflows for business enterprises have included the printing press (1440), the telegraph (1837), the telephone (1876), the computer, and now the Internet and mobile ecosystem. The following graph is a large oversimplification and focuses on a narrow area to demonstrate the concept.

It’s dangerous to discuss this without being accused of being a luddite, as a lot is changing around us, but I believe we are at a point of time where the fundamentals are going to stay the same for a long time around the core of how the web and mobile work. I don’t agree with the second half of this article at all, but the first part is pretty good in giving airplane technology as an example to think about this. For 40 or 50 years, airplanes had gotten safer and faster and more awesome each decade, with the turbo prop and then the jet engine and what not. As an engineer in the 1950s, most assumed that we’d be going at Mach 3 within a couple decades, and TWA was already taking commercial orders for people to fly their planes to the moon (this was just assumed to be something that would happen, apparently). It turned out, however, that the laws of physics and what was generally possible and comfortable within the framework of energy expenditure meant that we hit the peak commercial speed around the late 1950s with the Boeing 707. In fact, the new 787 is actually a slower plane.

If that author and many others I know are right, the basic information technology framework of being able to access and collect and process distributed data, and how the web works, may have been this one time shift in infrastructure that could look pretty similar even many decades from now, just as airplanes are very similar to 50 years ago.

And if that is true, it means the next decade is really important in business! Because while perhaps most of the new consumer platforms that should exist given this infrastructure have mostly been built (Google, FB, Amazon, now Uber, etc.), it’s clear that the enterprise platforms needed to upgrade all the major industries — industries such as government, finance, healthcare, energy, education, or others — have not been built. Platforms in these industries will help these institutions share and use their data to its fullest potential, and will enable a fundamental shift in how the industries work and who captures margin. Not only will building them help make these huge industries work a lot better and spread innovation, but there’s also a good chance that their creators will own these platforms for a very long time. This makes them very valuable — ironically, less disruption to how the world works means the existing companies are worth more.

There is a lot of money flowing around SV, but I think focusing on this reality is important — there should probably be even more money invested into what we are doing right now if it’s true that there has been a major paradigm shift that hasn’t worked its way through the economy yet AND is a big one-time shift. If you look how small the amount of money is going into this versus how much capital there is in the world and what the shift impacts, it’s actually really tiny. Of course, only the very best technology and business teams working for years towards the best ideas in these industries will win and create a category defining company that will be around for decades, but there may be a lot of these.

I was sharing my thoughts on this with Peter Thiel at breakfast this week, and he had a clear way of capturing the dynamic. Companies are either short or long innovation. Clearly Facebook and Google are innovative places with lots of amazing people, but if you are a large shareholder of GOOG or FB today, you are short innovation in search and social networks. If there is going to be a ton of innovation in these areas, these are much riskier stocks to own. Many great companies are long innovation for a few years — they are creating something new and proving it works. Then, while they may keep innovating and the people running them may be very innovative, shareholders are really mostly short innovation, as they don’t want the platform disrupted from everything going on outside the company.

This is an important thing to think about as a tech investor, as many of the later stage tech investments may actually be short innovation — that is where the bulk of the money goes into our space. It’s a useful model as sometimes we may be long innovation in one area but short in others, and we should be honest about which bet we are making.

If we are right and are able to distribute a lot of stock to our LPs in the future as our top big-industry platform companies succeed as standalone entities, all of us will end up in a financial position where we will be hoping there isn’t a lot of innovation that once again changes the fundamental structure of the web and mobile ecosystem and what’s possible in business. (I will probably be rooting for new innovation anyway, because I can’t help myself, but financially we’d all be aligned against it). Fortunately, for now, we are all very long innovation at our fund — that is more fun, and we are very excited to prove to the world how some of these old industries should work.

And I think we are set up to do just that in a lot of areas, assuming our most successful companies are able to keep learning and growing, and aren’t destroyed by the challenges of their early success.